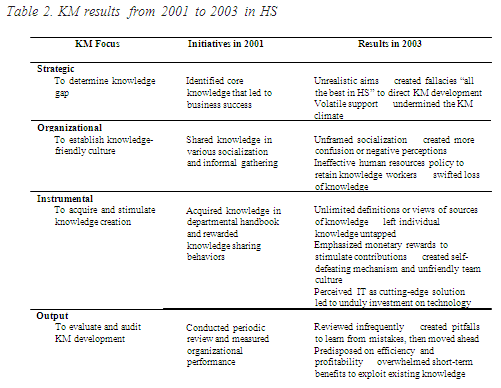

the KM initiative with a focus on the following four main aspects: strategic, organiza- tional, instrumental, and output.

In the strategic aspect, it was considered that knowledge available and possessed at HS would fall short of the core competence necessary for business success (e.g., chic product design). Therefore, effort was needed to fill this gap by acquiring knowledge from both external and internal sources. From the organizational side, it was thought that knowledge was more valuable when it was shared and exchanged. Thus, a knowledge- friendly culture needed to be promoted through encouraging employees to socialize and share their ideas and thoughts such that new knowledge could be created to broaden their knowledge repositories. At the base level, it was determined that knowledge had to be acquired, stored, and disseminated in a systematic way to enable employees to access and reuse it easily. In doing so, essential knowledge, such as experienced practices in production skills and innovative ideas in product design, could be captured and recorded. Individual employees or teams who contributed knowledge useful and relevant to HS were to be rewarded. Last but not least, from an output perspective, it was realized that periodic reviews were crucial for evaluating KM effectiveness and for devising subsequent corrective action, if necessary. Performance indicators such as production efficiency, adoption rate of good practices identified, and clients’ satisfaction were required.

A detailed implementation plan was devised based on the above analysis, which was then agreed to and approved by the top management of HS. The KM program was officially launched in April 2002.

CURRENT CHALLENGES/PROBLEMS FACED BY HS

After 15 months, HS found that the KM initiative did not generate the positive impact on organizational performance as expected. Organizational performance remained stagnant, revenue continued to decrease, and staff turnover rate stayed high. Our involvement with HS as an external consultant began after the CEO had determined to find out why and/or what happened. Our assistance to HS was clear — to investigate the situation, to uncover the mistakes, and to look for remedies. A series of semistructured interviews with key employees in the managerial, supervisory, and operational levels were therefore conducted. Table 2 summarizes our findings.

As seen, a good start does not guarantee continuity and success (De Vreede, Davison, & Briggs, 2003). First, two crucial reasons were identified as to why HS was unable to bridge the knowledge gap. They were (1) the top management was too ambitious or unrealistic to grasp and incorporate the “best” knowledge in industry into the company and (2) their insufficient role support in encouraging the desired behavior. Similar to many other KM misconceptions, top management wrongly aimed at incorpo- rating other enterprises’ best practices (e.g., product design of the fad) or success stories (e.g., cost cutting and streamlining operational processes) into its repositories without considering the relevance, suitability, and congruence to its capabilities. Therefore, this “chasing-for-the-best” strategy soon became problematic and departed from its KM goals. HS did not gain business advantages, such as unique product design and value- added services to customers, and were still unable to respond to the marketplace swiftly.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Knowledge is increasingly recognized as providing a foundation for creating core competencies and competitive advantages for organizations, thus effective knowledge management (KM) has become crucial and significant. Despite evolving perspectives and rigorous endeavors to embrace KM intentions in business agendas, it is found that organizations cannot capitalize on the expected benefits and leverage their performances. This is a case study of an organization in Hong Kong. It is a typical organization with a strong awareness and expectation of KM, yet its program failed within two years. Our findings show that KM activities carried out in the organization were fragmented and not supported by its members. Based on this failure case, four lessons learned are identified for use by management in future KM initiatives.

BACKGROUND

Founded in 1983, HS (the actual name of the company is disguised for confidenti- ality) is a Hong Kong-based enterprise with a production plant in mainland China. HS is primarily engaged in the production and export of handbags and leather premium products to the United States and European markets. The current CEO is the second generation of the founder. Like many companies in Hong Kong, HS centralizes all its strategic planning and decisions, as well as sales and marketing functions at its head office in Hong Kong while doing the production and assembly work across the border for low production cost. Appendix 1 is the organizational chart of HS. It is found that the head office has 10 staff including a CEO, a general manager, a sales manager, an operation manager, and six other administrative staff. The production plant in China has 450 staff including 40 managerial, supervisory, or administrative staff and 410 skilled workers. Over the years, HS has expanded its range of products and production capacities and resources in order to seize market opportunities and has enjoyed quite healthy growth in terms of sales turnover and profits.

SETTING THE STAGE

Business began declining with double-digit revenue losses in 1998. This was primarily attributed to the fierce competition in the markets and soaring production cost. For example, some competitors were offering drastic price cuts in order to obtain business contracts. Also, new product designs did not last long before being imitated by the competition. The CEO and the senior management team began planning the future of the company and to look for ways to improve the efficiency and productivity of its employees. Business continued to deteriorate, so that by 2001, in order to find out what had gone wrong, the CEO formed a strategic task force consisting of all managers in Hong Kong, several key managers responsible for the production plant in China, and himself to look into the matter. After two weeks of exploration (including observation and communicating with other staff in the company), the strategic task force concluded that knowledge within the organization was ineffectively managed; specifically, there was low knowledge diffusion from experienced staff to new staff, and high knowledge loss due to turnover. Driven by traditional management philosophy, the CEO and the strategic task force believed that they understood the organizational context better, and thus decided to undertake an in-depth investigation through internal effort instead of hiring an external consultant.

CASE DESCRIPTION

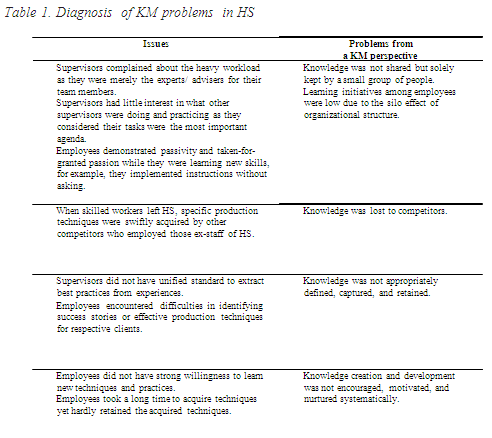

In June 2001, the strategic task force carried out investigation, observation, and interviews of employees in various departments. After three months, they identified the knowledge management (KM) issues summarized in Table 1.

From these findings, the strategic task force determined that open communication and discussion was necessary and effective to further examine the KM problems, and therefore called for a couple of meetings with managers and supervisors. In order to encourage open discussion, the meeting was conducted in an informal manner instead of the frequently used formal discussion (such as predefined order for reporting departmental issues). Furthermore, the room setting was changed with seats arranged in a circle to allow everyone to see each other and a flip chart was made available to jot down immediate thoughts. More importantly, everyone was encouraged to express his/ her thoughts, opinions, and feedback from a personal perspective or collective stance (e.g., comments from subordinates).

The results of the meeting were encouraging as many participants expressed their opinions and comments eagerly. In particular, staff in the meeting agreed that KM was neither an extension of information management nor solely a technology application to capture, organize, and retrieve information or to evoke databases and data mining (Earl & Scott, 1999; Thomas, Kellogg, & Erickson, 2001). Instead, knowledge was embedded in people (e.g., skills and actions), tasks (e.g., production process), and the associated social context (e.g., organizational culture) that involved communication and learning among loosely structured networks and communities of people. Therefore, individuals/ employees were crucial to the implementation of KM initiatives by utilizing their knowledge and skills to learn, share, combine, and internalize with other sources of knowledge to generate new thoughts or new perspectives.

With the above results, HS decided to devise and launch a KM program with an aim to institutionalize knowledge diffusion among employees and leverage knowledge creation for quality products. Instead of a top-down approach of policy making, the management adopted a middle-up-down approach (Nonaka, 1994) with supervisors as the major force to leverage and promote KM throughout the organization. To enhance acceptance and lessen resistance to change, HS chose a new product series to try out

Second, the mere presence of KM vision is not sufficient to guarantee KM success. Most employees commented that top management involvement in the KM implementa- tion was volatile and appeared to be a one-shot exercise (Gold, Malhotra, & Segars, 2001). For example, the KM program started well with noticeable initiative to identify untapped knowledge from various sources, yet fell behind the expected goals as top management involvement was remote (e.g., leaving the KM effectiveness as departmental responsi- bility) and support was minimal (e.g., time resources available for knowledge sharing and creation). Thus, the two factors directly hampered the employees’ dedication and belief in KM as a significant organizational move.

Third, from the organizational aspect, even though various social activities such as tea parties were used to foster a friendly and open organizational culture, we found that most of these knowledge-sharing activities were futile because no specific and/or appropriate guidelines for such sharing had been devised (Nattermann, 2000). As a result, instead of having discussions that were directly related to tasks, or least contributed to idea generation, frequent chats (e.g., gossiping) among employees and wandering around were found. Many employees were confused with what the sharing was all about. Some employees even perceived KM negatively as interfering with activities important to their daily tasks, creating resistance to participation in what was perceived to be a temporary fad.

Fourth, the instruments used to help acquire and stimulate knowledge creation and sharing encountered problems during implementation. The fallacy of knowledge acqui- sition with reliance on external sources (such as the existing practices addressed by competitors) undermined employees’ intent to explore the available but untapped knowledge resident in their minds (Bhatt, 2001; Nonaka, 1994). The use of information technology to drive knowledge storage and sharing, in principal, was conducive to employees. Yet, the silo organizational structure of HS with disentangled databases for knowledge capture caused more harm than good. Some employees asserted that they did not have the incentive to access or utilize the departmental knowledge handbook and procedural guidance (available from databases) as it is a time-consuming endeavor to dig from the pile of information. Some employees found knowledge incomprehensible as it was presented and stored in various formats, with jargons and symbols that were neither standardized nor systematized across departments.

Fifth, although a reward system was established for knowledge creation and/or sharing, the emphasis on extrinsic terms, such as a monetary bonus, turned out to have an opposite and negative effect on cultivating the knowledge-sharing culture and trust among employees. Some employees commented that knowledge should be kept as personal interest (i.e., not to be shared) until they felt that they could get the monetary reward when shared or recognized by management. Other employees found that harmony and cohesiveness within the team or among colleagues were destabilized as everyone maximized individual benefits at the expense of teamwork and cooperation.

Sixth, there was a misleading notion that IT could be “the” cutting-edge solution to inspire KM in organization. Despite the introduction of IT tools to facilitate knowledge capture, codification, and distribution, it was found that IT adoption and acceptance remained low due to employee preference for face-to-face conversation and knowledge transfer instead of technology-based communication, and the general low computer literacy that intensified the fear of technology. In addition, given the insufficient support from management for IT training and practices, employees, particularly those who had been with HS for a long time, had strong resistance to new working practices for facilitating KM.

Seventh, it was noted that the KM initiatives were left unattended once imple- mented. It remained unclear as to how to exceed existing accomplishments or overcome pitfalls of the KM initiatives, as there was no precise assessment available. For instance, the last survey evaluating the adoption of best practices from departmental knowledge was conducted a year ago, without a follow-up program or review session. Another example was that the currency and efficacy of the knowledge recorded in the departmental handbook appeared obsolete as no procedures were formulated to revise or update the handbook.

Last but not least, an undue emphasis and concern with the “best-practice” knowledge at HS to improve short-term benefits (e.g., to exploit existing knowledge in order to achieve production efficiency) at the expense of long-term goals (e.g., to revisit and rethink existing knowledge and taken-for-granted practice in order to explore innovation and creativity opportunities). Some employees pointed out that they were inclined to modify existing practices rather than create new approaches for doing the same or similar tasks as recognition and positive impacts can be promptly obtained.

EPILOGUE

To date, KM is considered an integral part of a business agenda. The dynamics of KM as human-oriented (Brazelton & Gorry, 2003; Hansen, Nohria, & Tierney, 1999) and socially constructed processes (Brown & Duguid, 2001) requires an appropriate deploy- ment of people, processes, and organizational infrastructure. This failure case presents the challenges that could be encountered and coped with in order to accomplish effective KM implementation. The people factor is recognized as a key to the successful implemen- tation of KM from initiation, trial, to full implementation. KM is a collective and cooperative effort that requires most, if not all, employees in the organization to participate. KM strategy and planning should be organized, relevant, and feasible within the organizational context. One’s best practices and winning thrusts may not be well fitted to others without evaluation for fit and relevance. A balanced hybrid of hard (e.g., information technology) and soft infrastructure (e.g., team harmony and organizational culture) is needed for success.

LESSONS LEARNED

Knowledge management is increasingly recognized but its challenges are not well understood. To institutionalize a KM program, organizations can draw lessons from this failure case so as to construe what imperatives are needed and what mistakes should be avoided. Management issues and concerns are highlighted as follows.

Lesson 1: Start with a KM Plan Based on Realistic

Expectations

The mission and behavioral intentions of leaders have a strong impact on employ- ees and where to aim and how to roll out KM processes (KPMG, 2000). In this case, it is appreciated that top management recognized its organizational ineffectiveness and initiated a KM plan as a remedy. We suggest, however, that planning based on unrealistic expectations undermined its ability to successfully direct future actions. Therefore, management has to be reasonable in setting KM goals, perceptions, and beliefs. It is suggested that a feasibility assessment of organizational infrastructures (e.g., financial resources, technology level) and organizational climate (e.g., employees’ readiness to KM, resistance to change) be conducted to define the KM principles and goals. Inspirational aims, which can be reasonably and feasibly accomplished, encourage employees to assess their personal knowledge and transfer others’ knowledge when it is shown to enhance existing practices and can help meet new challenges.

Lesson 2: Management Support is a Strong, Consistent, and more Importantly, Cohesive Power to Promote KM

It is evident that vision without management support is in vain and temporary. As valued most by the HS employees, continuous corroboration from top management is indispensable to motivate their commitment toward knowledge-centric behaviors for long-term competitiveness (Lee & Choi, 2003). Therefore, beyond visionary leadership, management should be willing to invest time, energy, and resources to promote KM. At its core, management could show their enthusiasm in a boundless and persistent way, including vocal support, speech, inaugural memo, and wandering around different business units to invite impulsive idea generation and knowledge creation from all levels of staff. Also, management could champion the KM process and lead by example with employees who are receptive to KM.

Lesson 3: Integration of Monetary and Nonmonetary

Incentives

To stimulate KM behaviors, specifically sharing and creation, it is important to assure a balanced reward system integrating monetary and nonmonetary incentives that fit various forms of motivation (Desouza, 2003). In the beginning of the KM programs, employees needed to be shown that personal benefits could be obtained from KM success with improvement in products, processes, and competitiveness. Therefore, rewards that are direct, monetary-based, and explicit are useful. For this, management can provide salary increase or promotion. With the passage of time, rewards could be extended to something implicit. For instance, management can publicize those employ- ees’ names and respective ideas that contributed to organizational processes, or provide skills-enhancement program to enable employees to see their importance with extended job scopes. Moreover, management can consider rewards systems geared toward individual or team achievement so as to encourage more interaction, creativity, team- work, and harmony among people.

Lesson 4: KM has to be Cultivated and Nurtured, which is not a Push Strategy or Coercive Task

As shown in this case, KM is not a singly motivated exercise. It requires a collective and cooperative effort to put into effect various resources. Other than the vision and top management support, operational staff can greatly affect the success of the KM program. Their influences affect attitudes, behaviors, and participation in KM and could exert positive impacts on KM effectiveness if managed properly. For attitudinal changes, efforts have to remove or at least alleviate employees’ negative perception toward KM. For example, the fear and misconception that KM is a means to downsize organizations for efficiency or as heavy workload which requires much IT expertise. For behavioral changes, we highlight a supportive working environment where employees can have ample time to engage in KM endeavors, such as sharing and creation, a fair and positive culture where everyone is valued and encouraged to contribute to KM effectiveness, is needed. To encourage participation, pushing or mandatory activities are least effective. Coupled with the rewards systems, employees should be inspired to take risks as learning steps for KM success. Unexpected failure or unintended results may cause management to call for a break to identify the causes and remedy solutions. Do not quit or blame, otherwise, mutual trust and commitment to work with the KM processes will be lessened.

REFERENCES

Akbar, H. (2003). Knowledge levels and their transformation: Towards the integration of knowledge creation and individual learning. Journal of Management Studies, 40(8), 1997-2021.

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D.E. (2001). Review: Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Quar- terly, 25(1), 107-136.

Bhatt, G.D. (2001). Knowledge management in organizations: Examining the interaction between technologies, techniques, and people. Journal of Knowledge Manage- ment, 5(1), 68-75.

Brazelton, J., & Gorry, G.A. (2003). Creating a knowledge-sharing community: If you build it, will they come? Communications of the ACM, 46(2), 23-25.

Brown, J.S., & Duguid, P. (2001). Knowledge and organization: A social-practice perspec- tive. Organization Science, 12(2), 198-213.

Desouza, K.C. (2003). Facilitating tacit knowledge exchange. Communications of the ACM, 46(6), 85-88.

De Vreede, G.J., Davison, R.M., & Briggs, R.O. (2003). How a silver bullet may lose its shine. Communications of the ACM, 46(8), 96-101.

Earl, M.J., & Scott, I.A. (1999). What is a chief knowledge officer? Sloan Management Review, 40(2), 29-38.

Gold, A.H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A.H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organiza- tional capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185-214.

Hansen, M.T., Nohria, N., & Tierney, T. (1999). What’s your strategy for managing knowledge? Harvard Business Review, 77(2), 106-116.

King, W.R., Marks, Jr., P.V., & McCoy, S. (2002). The most important issues in knowledge management. Communications of the ACM, 45(9), 93-97.

KPMG Consulting. (2002). Knowledge management research report 2000.

Lee, H., & Choi, B. (2003). Knowledge management enablers, process, and organizational performance: An integrative view and empirical examination. Journal of Manage- ment Information Systems, 20(1), 179-228.

Nattermann, P.M. (2000). Best practice does not equal to best strategy. The McKinsey Quarterly, 2, 22-31.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14-37.

Thomas, J.C., Kellogg, W.A., & Erickson, T. (2001). The knowledge management puzzle: Human and social factors in knowledge management. IBM Systems Journal, 40(4), 863-884.