Introduction Deloitte & Touche is one of the U.K.’s largest firms of chartered ac- countants and management consultants, with twenty-four offices and over 6,500 staff nationwide. The U.K. practice of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (DTT) is a global leader in professional services with over 72,000 employees in 129 countries. With the mergers and acquisitions The views expressed in this chapter are the author’s own, and not necessarily those of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (DTT) or any national practice thereof. No legal liability is accepted by the author, DDT, or Deloitte & Touche for any use made of this work.

The author wishes to thank Laurence Capus for her contribution to a first draft of this chapter. of recent years, and the drive to generate new business, the interna- tional firm has been able to consolidate its position as a leading prac- tice, with worldwide fee income of over $7 billion. DTT provides a range of services delivered through specialist, multifunctional teams, designed to meet the requirements of the principal business sectors that we serve. These teams, which are organized on a national basis, can draw on a complete range of assurance and advisory, tax, corpo- rate finance, reorganization, insolvency, forensic, management solu- tions, management consultancy, and other business services, thus bringing together our expertise in each sector to benefit clients. We are one of the global leaders for audits of the world’s largest companies, and our largest clients include major companies from all industry sectors. This chapter explains the use of CBR in a specific business problem domain, namely, internal control evaluation, draw- ing on the experience from Deloitte & Touche UK.

The Problem

The Cadbury Committee established the UK Code of Best Practice on Corporate Governance for business in 1992.

The Code of Best Practice states that UK company directors should report on the “effectiveness” of their company’s system of internal control. An opinion on the ef- fectiveness of the system of internal control is not required, but an in- creasing number of UK companies give such an opinion. However, there was no general guidance on how these reports on effectiveness should be done or even on the form or content of the re- ports until a Joint Working Group produced the “Internal Control and Financial Reporting” document in December 1994. This document fo- cused more on a subset of internal control, namely, internal financial control. The principles explained in this document have been relevant to all UK business enterprises. The “Internal Control and Financial Reporting” document described some general principles, but the ex- act formats of companies’ directors’ statements were not prescribed, although it was suggested they might appear in separate statements or other reports than financial reports.

Since then it has been recommended that annual reports for UK companies include specific statements: these statements should confirm that the company’s directors are responsible for the company’s system of internal financial control. The statements also should describe the key control elements that the directors have set up, warn that these key con- trol elements can only give “reasonable and not absolute assurance against material misstatement or loss,” and attest that directors have re- viewed the effectiveness of the system of internal financial control. The different criteria for assessing effectiveness may be categorized as:

■ The company’s control environment. These elements may include controls regarding management involvement in business opera- tions and monitoring progress, control over transactions, ade- quacy of division of responsibilities, and appropriateness of plan- ning and implementation.

■ Identification and evaluation of risks and control objectives. These el- ements may include controls over the appropriateness of business systems and risk analysis processes.

■ Monitoring and corrective action. These elements may include the level of compliance with control criteria, reviews and checks, levels of reconciliations, scope and frequency of evaluations, and appro- priateness of internal audit.

■ Information and communication. These elements may include ap- propriateness of flows of internal and external information, use of IT, completeness and timeliness of information, and appropriate- ness of follow-up actions by management.

■ Control procedures. These elements may include control over viola- tions of relevant laws and regulations, general computer controls in- cluding access to data, control over financials (such as treasury, credit given to customers, inventory, etc.), and cash management in general.

■ Appropriateness of reporting. These elements may include appropri- ateness of reporting approaches, processes of reporting to the Board, reporting of legal and accounting developments to senior management, and exception reporting. Although these criteria may seem to be quite comprehensive, the “Internal Control and Financial Reporting” guidance did not include examples of how statements by company directors on internal finan- cial control should be made. However, the same guidance advises that the company statements should include an explanation of the steps taken by the company to:

■ ensure an appropriate control environment,

■ state the processes used to identify major business risks,

■ assess the information technology in place,

■ understand the major control procedures, and

■ explain the monitoring system used by the Board to check that the system is effective.

To summarize, directors of U.K.-based companies are responsible for establishing and maintaining appropriate internal control systems. As there is no general or standardized approach for doing so, judgments must be made not only to assess the anticipated benefits and costs of management information and of control procedures, but also in the control estimation approach itself. As a consequence, an appropriate way to help directors examine on a confidential basis their business’s level of internal control is to compare, or benchmark, their operations with other companies, whether these companies are competitors or not. In this way, directors can analyze where their internal control strengths and weaknesses are most significant so that action can be taken to es- tablish and maintain appropriate internal control systems. Rule-based artificial intelligence techniques have helped Deloitte & Touche clients to design and run applications in business areas where decision making has been relatively well structured and easily transferable into formalized rule-based models.

The fact that standard business procedures are frequently highly structured or semistructured has spawned the initial rush of successful rule-based applications. However, the situation is different when dealing with unstructured business domains such as internal control, where expertise is scarce, expensive, and difficult to formalize. There is still a need to support business decision making for internal control, as it is a problem domain not bounded by rules, although there are as many different cases of internal controls as there are companies. Any rule-based processing to tackle internal control evaluation would raise some doubt, as rules do not lend themselves to capturing tacit knowledge of volatile business domains dynamically and combining different experts’ views.

Most of the present business expertise in inter- nal control evaluation exists in the form of cases rather than procedures that can be more easily converted into rules. One means of approaching the problem of translating procedures would be a solution consisting of the provision of a case library of expertise. CBR is well suited for this approach for the reasons explained in the next section.

The Knowledge Management Solution

CBR is an appropriate approach to deal with internal control since experience drawn from specific business case studies is in most in- stances more valuable than generalized textbook knowledge. At the same time, internal control evaluation is a domain where there is a potential combinatorial explosion because of the existence of many features associated with each case of internal control.

By finding the case closest to a specific business under evaluation, CBR shows the key questions that lead to benchmarking the problem, rather than a battery of standard parameters that may have nothing to do with the problem. Accountants investigating adequacy of levels of internal controls rely more frequently on examples than rules, especially when the repository of knowledge lies in the informal domain. As there are no generally accepted and reliable rules for internal controls, accoun- tants often have to rely on hints, clues, or assumptions.

Until now, expertise in internal control evaluation has been developed by the continual confrontation of the accountant with many varied busi- ness cases, and the clues for evaluating internal controls lie hidden in large information bases. As there are often similarities in different business cases, if presented to the accountant, these similarities can help not only support but also corroborate judgment. In those in- stances, cases are often used to validate and even justify the experts’ views. In this way, a CBR approach can support a consistent level of business decisions. A CBR approach in internal control can also be most helpful since this problem domain evolves very rapidly as business patterns change continuously. CBR makes the process of acquiring internal control ex- amples more natural, and obtaining high-level rules of thumb or heuristic knowledge about the domain is made easier. Case-based in- put avoids the translation of auditing rules of thumb into inference mechanisms that may lead to inconsistencies or loss of tacit knowl- edge. Case-based input also allows accountants to relate to typical or atypical cases rather than to hypothetical models.

The CBR model allows business cases of internal controls to be deleted as they become obsolete, and fictitious cases may be added to complete the coverage of the problem domain. Using past illustrations of internal controls, business experts will, in most examples, prefer to refer to these cases by using idea association. Indeed, the confidence in the CBR application will tend to increase in such circumstances.

Expected Benefits

One of the main reasons for using CBR at Deloitte & Touche for busi- ness domains such as internal controls, and fraud detection in partic- ular, is that the case-based model explicitly combines searching with learning.5 Using CBR in internal control evaluation can give users ac- cess to deeper knowledge and more relevant reasoning about the prob- lem in the form of a data laboratory exercise. For example, in browsing a cluster tree discriminating between in- ternal control cases, the user observes the discriminators or nodes that are most information-rich, or meaning-rich.

These meaning-rich as- pects of a case-based approach may be crucial to the user for a more appropriate level of interaction, by which the user is encouraged to explore the problem domain until an appropriate solution is gener- ated from the search and learn processes. By recollecting past cases of internal control, reasoning can be directed because there is a compre- hensive path or trail laid out along which ideas and concepts natu- rally flow. In contrast to the result orientation of traditional rule- based approaches (where in most instances only a tracing facility is available), the case-based searching and learning approach has a critic-orientation emphasis. Both rule-based and CBR systems may contribute to increased consistency in business decision making in different ways: traditional systems have attempted to automate activities where business exper- tise is crucial, whereas CBR can be applied in business areas for which human intelligence needs to be augmented and amplified.

Expertise enhancement has been one of the major drivers behind the ControlSCAPE application designed by Deloitte & Touche. Learning about internal control is a crucial ingredient in the reasoning process, but often learning requires several iterations of problem solving and restructuring of business knowledge in the light of new experiences. Human problem solving in loosely structured busi- ness domains may falter when people must rely on memory to retrieve appropriate solved cases. This is especially true for experts whose heuristic reasoning depends on patterns of data embedded in past business cases. For these reasons, it also makes sense that ControlSCAPE could accelerate knowledge transfer, help staff share experiences, and also preserve knowledge gained in the corporate environment. These aspects are especially relevant to people dealing with unstructured business knowledge, since a large part of their tasks relies not only on objective information but also subjective interpretation of it.

It is in this context that Deloitte & Touche decided to design ControlSCAPE either as a directing system (using internal control cases to provide the user with simple adapted solutions from past cases relevant to the case under scrutiny) or as an indicating system (giving the user an opportunity to discover knowledge from cases that are “neighboring” the problem). In this way, ControlSCAPE would emphasize accountants’ analogi- cal problem solving and as a consequence help them reach more in- formed decisions about appropriateness of systems of internal control. ControlSCAPE was designed to encourage accountants’ imitation (ap- plying solutions to the current problem by referring to past solved cases), opinion making (searching for a clue that could lead to a solu- tion to the problem), and insight (giving a greater understanding of the problem domain by scanning through pertinent cases).

Thus, the case-based analogical reasoning in internal control provides an op- portunity for the business user to justify and support his or her deci- sion when the domain is too complex or when there is a need for con- flict resolution, which could eventually cost the client dearly.

The Team

The team consisted of the partner in charge (Martyn Jones, National Audit Technical Partner for the U.K. firm) and a member of staff (Olivier Curet, Senior Manager), supported by several consultants. The product champions have had extensive experience with the use of CBR and have been a driving force in the U.K. firm behind the design, im- plementation, and evaluation of specific knowledge-based systems and especially case-based approaches to business problem domains.

These problem domains have included the detection of management fraud, the detection of transfer pricing strategies, the identification of invoice discounting strategies, and the evaluation of trade missions.

Implementation Plan

The first part of the methodology consisted of case feature definition. Deloitte & Touche had already designed a method called “ICAP” (Initial Case Acquisition Process) used during our previous CBR- related work for applications mentioned earlier. The role of ICAP was to construct a set of potential case descriptors by circulating a ques- tionnaire that collected key features from the firm’s top experts. Initially, the features suggested arose from past cases, which allowed accountants to input their knowledge in a less constrained way. The resulting set of features was then recirculated to permit the experts to change, amend, or delete any features they felt were inappropriate, and the process was repeated until the different experts agreed. The amended form was circulated again to all the experts who crafted the questions in the first place, until the final version was agreed (vali- dated).

This “semi-Delphic” process allowed the users and designers to agree on the features that should be used to characterize cases and also to decide the types of cases that should be collected. After the feature calibration was validated, ICAP made it necessary to collect further cases on the basis of the agreed set. The purpose of this “case stabilization” was to collect a sufficient number of cases to obtain an appropriate coverage of the problem domain. Issues such as the effects of case aggregation (for example, is there a target number of cases to collect?) and case duplication (for example, what should be done about redundant cases?) were tackled.

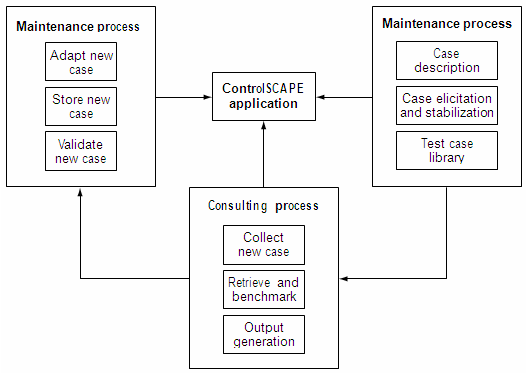

Thereafter, the reference case evolved with use over time, and the application was tested con- tinuously as it expanded. Once the ControlSCAPE case base was stabilized, it became the case library, and the application was ready for implementation. (The sys- tem architecture is shown in Figure 6.1.) The most appropriate method of case retrieval was decided. This included deciding the rela- tive importance (or weights) of features in case retrievals and whether weight vectors should be prescribed or left open for users to choose.

The flexibility of querying the case library was also examined. Other issues examined included case adaptation, when a new case should be stored and by whom, who is responsible for ensuring that the system has been “trained,” what kind of user training is required, and who should be responsible for the continuous evaluation of the system.

The ControlSCAPE Development Group’s role was to coordinate the over- all process and collect cases.

Hardware and Software

We evaluated several CBR development tools and examined how our major competitors used CBR within knowledge management processes. Five of the six main accounting and consulting firms are known to use CBR. These are Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (audit), Andersen Consulting (linking CBR and virtual reality), KPMG and PriceWaterhouseCoopers (help desks), and Coopers & Lybrand (risk and control).

Deloitte & Touche (U.K.) and Coopers & Lybrand (Germany) used the ReMind CBR tool, while the other firms used eGain’s CBR tools.6 As part of the ControlSCAPE project, it was necessary to choose ei- ther to have a complete in-house system or to build an application with an existing CBR tool. The advantages of using an off-the-shelf tool allowed the ControlSCAPE Development Group to focus on the methodology, case collection, and subsequent customization to client requirements. Programming a full CBR application, including the cre- ation of retrieval algorithms and user interface, would have signifi- cantly increased the risks associated with the project (such as going over budget or over time). The functionality required by ControlSCAPE was the capacity to retrieve cases using advanced retrieval strategies (based on induction rather than nearest neighbor), and the capacity to allow the fine- tuning of case representation (by defining symbolic values, for example).

ReMind had already been successfully used in the firm during the early 1990s for prototypes. It was felt that for working on a standalone basis, for a very specific business problem, and working with a cen- tralized case library, ReMind had the functionalities we were looking for despite its drawbacks. The system can run on a standard notebook computer.

Case Acquisition

During the ControlSCAPE case-base design phase, internal control cases were carefully defined and collected to ensure coverage of the business problem domain. To start with, the first part of the ICAP process was the result of a brainstorming session with several of the firm’s top experts in the audit field, mainly from U.K. and U.S. firms. Specific discriminators about internal controls emerged from this ex- ercise; and after several sessions over a few weeks, some specific ques- tions were repeated and patterns emerged when experts were asked to think about past cases.

At the end of this first process, the series of questions that had been formulated were clustered around the Cadbury Report framework, including:

■ control environment,

■ identification and evaluation of risk,

■ monitoring and corrective action,

■ information and communication,

■ control procedures, and

■ other.

Structured interviews took place during the following part of the ICAP process. The selected audit experts were asked to fill in the questionnaire while thinking about past cases they had encountered, and to walk through it with the interviewer. Initially they were asked to talk about the general principles driving good or bad levels of internal con- trols, discern between several types of internal control environments, and relate these types to general audit principles.

After this process, the following five questions were asked:

1. Are the indicators of “good” or “bad” internal controls exhaus- tive? If not, please give an exhaustive list.

2. How do you find out about these “good” or “bad” internal con- trols? Directly, or through an intermediary or manager?

3. In general, what makes you happy that nothing unusual is go- ing on?

4. In general, what would alert you to types of unusualness?

5. Is there anything that is so universal an indicator of “good” or “bad” internal controls that it and it alone will cause you to re- think your approach to an audit?

Please list the indicators. It was also possible for interviewees to express their thoughts while completing the exercise. The process was set to last no longer than forty-five minutes and was conducted by individuals with little back- ground knowledge of internal controls: this way, an interviewer who had some knowledge of the domain could not lead the interviewee, or disagree with the interviewee’s comments during the interviews.

In this specific way, ICAP was used to define the criteria being used for each question and as a consequence to define more closely the case representation.

Case Representation

ControlSCAPE works on the basis of the interviewees’ perceptions of internal control matters, ranked from 0 (low) to 5 (high) using a mod- ified Likert scale. By representing and designing ControlSCAPE questions, it was dis- covered very early during the ICAP process that it was necessary to make a distinction on the questionnaire between the “true” and the “false” missing values. The true missing value (for example, N/A) is a value that is not available because it is not applicable to the case being collected. For example, a question refers to internal audit and there is no internal audit function.

The false missing value (for example, IK— insufficient knowledge) is used for a question that is applicable to the case, but the accountant does not know the answer or cannot remem- ber. For example, his or her investigations were not yet advanced enough to answer this question. The difference between the two is essential for two main reasons. First, it allows the discrimination between data that is not available but is still useful during the use of ControlSCAPE. Second, when the feed- back to clients is given, one of the first areas of concern may be to per- form further investigation for which the answers are IK.

As a conse- quence, two extra missing value categories were added to the questionnaire during the ICAP process, representing, respectively, not applicable and insufficient knowledge. It has been shown that experts are quite poor at weighting informa- tion accurately and that their answers to specific questions affect their measurement of other questions. Whenever experts give judgmental answers to soft issues, there is no way to split statistically the valid from the biased elements. This is why an overall evaluation field has been added to ControlSCAPE. This “heuristic link” could be statistically measured, but it would be difficult to validate.

For these reasons ControlSCAPE does not try to explain possible correlations between subjective answers.

Case Retrieval

ControlSCAPE includes a full list of features on internal controls (more than 350 parameters for 200 cases as of May 1998). Figure 6.5 provides a representative list of case features.

Case Adaptation

ControlSCAPE does no case adaptation. The problem is that appro- priate CBR adaptation approaches depend on the purpose of the system and its desired outcome. Cases of internal control can be seen as being too instrumental and only flat descriptions or snapshots of past instances, the definitions or even contexts of which may no longer be relevant to any business. If all the data is quantitative, CBR and its adaptation process may be relatively straightforward. In contrast, it is far less easy to adapt business cases when the domain knowledge con- tains soft information, such as an expert’s judgments and perceptions, rather than hard, or factual, data. The generation of soft information-based business cases is used more to guide and suggest user reasoning and learning based on some relevant cases. If the cases contain mainly soft information, adaptation may be mainly user guided. In contrast, if the cases contain mainly fac- tual descriptions of past cases, they can be directly adapted to solve the present problem.

Case Retention and Maintenance

Maintenance issues include deciding when a case becomes obsolete, when new cases and/or features need to be added, and the criteria that dictate when to store a new case.

Only the case base administrator is authorized to maintain the case base. This greatly reduces the risks as- sociated with possible interference from other users who may input cases or delete previous ones unknowingly. Training has been given to other managers who can also operate the system when the adminis- trator is out of the office. All new cases that are investigated using ControlSCAPE for client assignment are input in the case base on a confidential basis. Only the senior manager or partner in charge of the application is authorized to request that new criteria be added to the application.

Interface Design

There was no specific interface design since the default interface of the ReMind tool was used. This is one advantage of using software that the firm already knew instead of programming and customizing a full application in-house. As the manager in charge of running the system knows the tool very well, it was felt that the interface did not need change, and efforts instead concentrated on case collection, process- ing, and output generation issues.

Testing

With regard to the evaluation phase, particular attention was given to both the accuracy of the case base (whether relevant cases are re- trieved) and usage (whether the correct decisions are reached on the basis of the cases recovered).

The approach used for evaluating ControlSCAPE was the same as for previous applications that the firm had built, including the fraud detection system. The problem with evaluating CBR knowledge management appli- cations is related to the understanding that the validation of the ap- plication is more complex than for conventional systems. A CBR ap- plication is more difficult to evaluate because new cases are input on a continuous basis and users’ expectations change with time. Furthermore, the evaluation of such systems in a business organiza- tion is critical because members of management need to know whether the time devoted to the project and the financial investment have been worth it. A few methods have been designed for CBR evaluation, either after implementation or during the development process. In our domain some business cases may be irrelevant to a particular end user, while different users may perceive the subjectivity inevitably included in cases in different ways. In effect, our CBR knowledge management systems contain layers of different experiences.

In some domains, features can encapsulate qualitative details, such as perceptions, understanding, and biases about specific problems. Although cases are not necessarily consistent with one another, they will make up a coherent encapsulation of the problem domain. One major aspect of CBR is that the case base is expanding all the time, so the results of searching the case base are time sensitive and user sensitive. All these factors influence the nature of the knowl- edge discovery process, and thus must be taken into account during evaluation. Since CBR solves problems by selecting similar problems or similar sequences of events, the business solutions generated may vary more because the cases used represent very different concrete business ex- periences. This is why a more holistic approach to the evaluation of ControlSCAPE was used, assessing both the accuracy of the system (that is, its reliability) and its effectiveness (its impact on the user and the organization). The accuracy approach to ControlSCAPE evaluation consisted of testing the number of successful hits (retrieving cases of the same type, on the scale from 1—seriously inadequate levels of control—to 7— world class). It was important to estimate the precision and noise when searching for and retrieving “appropriate” knowledge.

The precision of information retrieval has been considered as being the ratio of the number of items relevant to the user (hits), divided by the total num- ber of items retrieved. The noise of information can be considered as being the ratio of the number of items not relevant to the user (waste), divided by the total number of items retrieved.

Rollout and Benefits

Since ControlSCAPE was tested and validated, it was used in the London office. Initially it was applied to small-sized projects (mainly from the UK). After these few projects, no major amendments were requested.

Accountants discovered very early that ControlSCAPE had the following benefits:

■ The system enables any business control system to be measured on a scale from 1 to 7, taking the scales from the nearest neighbors. This benchmark is quite difficult to perform without ControlSCAPE.

■ ControlSCAPE facilitates internal and external benchmarking. It makes sense to benchmark among business units within the larger companies, and it also makes sense to benchmark any internal sys- tem with peer companies.

■ ControlSCAPE enhances judgments relating to quality of systems while identifying where further internal control inquiries need to be made, as well as identifying weaknesses.

■ ControlSCAPE can show where improvements in internal controls can be made by measuring the gap between the client’s level of con- trol and the “best in class.”

■ ControlSCAPE output facilitates the governance process by pro- viding succinct overview of strengths and weaknesses to the client company’s Board.

System Demonstration

The ControlSCAPE questionnaire is always completed to the fullest extent possible. The respondents’ first impressions are considered the most valuable. It is requested that in the first phases of opera- tion, parameters are neither deleted nor changed. It is advised that the ControlSCAPE questionnaire should take about forty-five minutes to complete if the respondents know the entity or group well. If several people come together to develop and answer shared views, more time will be required to facilitate discussion and consensus. Every effort is always made to complete the questionnaire in one session. The ControlSCAPE questionnaire may be completed by the accountant as part of a client service engagement or new business ini- tiative, or may be made available to clients to complete their own as- sessment.

In situations where clients complete the questionnaire, re- sponses are reviewed to ensure completeness and responsiveness to the intended control parameters. In all cases, the client service partner re- views the questionnaire for reasonableness and completeness, espe- cially if there are different cases collected about the client’s different subsidiaries worldwide. In completing the questionnaire, it is important to provide back- ground information about the case (type of entity, size of turnover, etc.).

This information will enable comparisons to be made not only against the database as a whole but also against specific subsets and combinations within the database, including industry sector, size, na- ture of the entity, type of entity, or even geographic location. The iden- tities of the entities in the case base are always kept confidential. After the team of accountants and/or client’s senior management have answered the ControlSCAPE questionnaire, the responses are in- put for benchmarking. The ControlSCAPE output includes a nearest neighbor analysis and profile that indicate which questions and an- swers were weighed most heavily in determining the cases that the cur- rent case most closely resembles. This provides the client with an over- all assessment of the internal control structure (whether it is underdeveloped, adequate, well developed, progressive, etc.), sugges- tions for improvement, and a comparison against industry averages.

The typical ControlSCAPE deliverable document includes a bench- marking report (analysis of ten nearest neighbors); graphical display indicating where the company falls on the scale, from seriously inade- quate to world class; profiling of key parameters used for analysis; identification of areas of insufficient knowledge; and comparison against average under each of the five Cadbury headings.

Conclusion

ControlSCAPE has shown that CBR is an appropriate approach to business problem solving when the problem domain is unstructured and involves significant amounts of tacit knowledge. The main benefit of ControlSCAPE is the significant added value it gives to Deloitte & Touche clients. The ControlSCAPE techniques, resulting audit work, and discussions always help the client identify control performance gaps. Workshops with clients can then be organized by holding one or more sessions with the client’s staff to generate ideas on control per- formance opportunities. Part of these sessions can be used to identify the change drivers and business objectives and then help brainstorm with the client on the aspects of the system of control that are strong, and on where it can be improved. Potentials for improvement are al- ways detected. A second benchmark can be done as a follow-up a few months after the first benchmark to see if the ratings improve.