EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This case study is aimed at developing an understanding of the various aspects and issues concerning the implementation of a knowledge-enabled customer relationship management (KCRM) strategy at a telecommunications company in a developing country. The KCRM program was composed of three major parts: enterprise data warehouse (EDW), operational customer relationship management (CRM), and analytical CRM. The KCRM initiative was designed to automate and streamline business processes across sales, service, and fulfillment channels. The KCRM program is targeted at achieving an integrated view of customers, maintaining long-term customer relationship, and enabling a more customer-centric and efficient go-to- market strategy. The company faced deregulation after many years of monopoly. The company initiated a customer-centric knowledge management program, and pursued understanding customers’ needs and forming relationships with customers, instead of only pushing products and services to the market. The major result of the case study

was that the KCRM program ended as an Information and Communications Technology (ICT) project. The company did not succeed in implementing KCRM as a business strategy, but did succeed in implementing it as a transactional processing system. Several challenges and problems were faced during and after the implementation phase. Notable among these was that the CRM project complexity and responsibilities were underestimated, and as a result, the operational CRM solution was not mature enough to effectively and efficiently automate CRM processes. Changing organizational culture also required a tremendous effort and pain in terms of moving toward customer- centric strategy, policy and procedures, as well as sharing of knowledge in a big organization with many business silos. Employees’ resistance to change posed a great challenge to the project. As a conclusion, the KCRM case study qualified as a good case of bad implementation.

INTRODUCTION

Business organizations are experiencing significant changes caused by the grow- ing dynamics of business environments. Organizations are faced with fierce competitive pressures that come from the globalization of economies, rapid technological advance- ments, rapid political and governmental changes, and increases in consumer’s power, sophistication, and expectations as customers become more knowledgeable about the availability and quality of products and services. Such environmental challenges place a huge demand on firms to remain flexible, responsive, and innovative in delivery of products and services to their customers (Drucker, 1995; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997).

The resource-based view of the firm recognizes the importance of organizational resources and capabilities as a principal source of creating and sustaining competitive advantage in market competition. According to this approach, resources are the main source of an organization’s capabilities, whereas capabilities are the key source of its competitive advantage (Grant, 1991; Davenport, 1995). Establishing an effective knowl- edge management capability is a challenge in 21st-century organizations.

The importance of customers to business firms has created tough “rivalries” among competitors over acquiring new customers or retaining/expanding relationship with current ones. In order to build good customer relations, it is necessary for companies to serve each customer in his/her preferred way, therefore requiring the management of “customer knowledge” (Davenport, Harris, & Kohli, 2001). Customer Knowledge (CK) is increasingly becoming a principal resource for customer-centric business organiza- tions. As a consequence, acquisition and effective usage of such knowledge is increas- ingly becoming a prerequisite for gaining competitive advantage in today’s turbulent business environments.

Establishing an effective KM initiative is a challenge for most organizations. Particularly difficult is the capture of tacit knowledge that resides primarily in the heads of experienced employees. Knowledge involves three overlapping factors, namely, people, organizational processes (content), and technology (ICT) and can be ap- proached in two ways:

• Personalization: human-based information processing activities such as brain- storming sessions to periodically identify and share knowledge

• Codification: systematic processes for regularly capturing and distributing knowl- edge

The personalization strategy is more focused on connecting knowledge workers through networks, and is better suited to companies that face one-off and unique problems that depend more on tacit knowledge and expertise than on codified knowledge. The codification strategy is more focused on technology that enables storage, indexing, retrieval, and reuse of knowledge after it has been extracted from a person, made independent of person, and reused.

Objective and Structure of the Case Study

This case study aims at developing an understanding of various aspects and issues related to the implementation of knowledge-enabled customer relationship management (KCRM) by a telecommunications firm in a developing country. The telecommunications company, referred to as Global Telecom (GTCOM) from now on, seeks to move from an engineering-led organization toward a customer-centric strategy as the backdrop for implementing the KCRM. The KCRM initiative was designed to allow GTCOM to automate and streamline its business processes across sales and service channels. The KCRM strategy was targeted at achieving an integrated view of customers, maintaining long-term customer relationship, and enabling organizational transformation from prod- uct-centric to customer-centric.

The case study starts by providing a background to the motivation for moving toward a customer-centric organization, followed by setting the stage to the case, and exploring the details of the case. Then, the chapter describes the current challenges facing the organization, and ends with a discussion and conclusions.

Methodology

In order to gain an understanding of the organization as a whole and the KCRM initiative in particular, 11 in-depth face-to-face interviews, and one in-depth telephone interview were carried out to solicit the viewpoints of the concerned managers from different managerial levels and business functions. In addition, appropriate organiza- tional documents and reports were consulted.

The interviews were systemically analyzed, and the result of the interviews was tape-recorded voice descriptions of the main aspects and issues when implementing the KCRM initiative.

BACKGROUND

Drivers for Becoming Customer-Centric

The telecommunications sector in this developing country was in a monopolistic position with respect to virtually all telecommunications, data transmission, and Internet services for many years. As part of the government policy to liberalize different business sectors, an autonomous body was established to regulate the telecommunications sector. The Telecommunications Regulatory Commission (TRC) by the end of 2002 issued expressions of interest for a second GSM license, and awarded a second license in 2004. The market was due to be fully open to competition in all telecommunications areas by July 2004.

Never had the external environment of GTCOM been so competitive, turbulent, and challenging with respect to attracting and keeping customers and controlling costs. The delicate market position of GTCOM, due to the liberalization of the telecommunications market, was aggravated by organizational dysfunction manifested by a strong hierarchi- cal structure, indigenous culture, and a product-centered business. The fear was that unless GTCOM undertakes substantial change, its competitors would move ahead and it would be left behind.

In an attempt to face the challenge, the main thrust of activities in the past months was to make GTCOM more customer friendly and efficient so that consumers will be less inclined to “jump out of the ship” and defect to new players in the market. As a result, GTCOM decided to adopt a knowledge-based customer-centric response strategy, that is, KCRM, in order to diffuse existing business problems and exploit future business opportunities.

The KCRM initiative targets the achievement of a more integrated approach toward serving customers through a multitude of channels. By implementing the KCRM program, GTCOM sought to transform its customer-centric data into complete knowl- edge, and to apply that knowledge to the development of a longer-term relationship with customers. The complete understanding of existing customers enables GTCOM to meet current market challenges and represents a new potential market and source of gaining competitive advantage, retaining existing customers, repeating profitable sales, increas- ing revenue, and improving customer satisfaction.

Corporate History

GTCOM came into being in 1981 as a national telecommunications shareholding company. GTCOM is now working toward meeting the demands of the new info- communications age — the convergence of communications, computing, entertainment, mobility, and information.

As one of the country’s largest organizations, GTCOM makes a difference in people’s lives. To improve this, besides creating business and employing citizens, it is committed to addressing the impoverished and underdeveloped sections of the commu- nity, and allocates 2% of its profits every year to educational, cultural, environmental, charitable, and social causes.

Type of Business and Products/Services

GTCOM is an integrated communications solutions provider that offers a wide range of products and services in the data, Internet, mobile telephony, and fixed telephony market segments.

In the Internet service provision market, GTCOM has services that include one-stop shopping, integrated services digital network (ISDN), messaging switching system (MSS), budget Internet-access service, and asymmetrical digital subscriber line (ADSL). In telephony, though the broadest market is fixed lines, mobile services grow ten times faster.

Organizational Structure

GTCOM is considered one of the largest companies in the region in terms of employees and revenue. GTCOM employs more than 2,000 employees with different skills such as engineering, ICT, business management, and support. The command structure of GTCOM is rather traditional, hierarchical, and “functional” in nature. In functional organizations such as GTCOM, work is conducted in departments rather than customer- centered business processes that cut across business functions. The organizational structure is composed of four hierarchical levels. The top level represents the board of directors and chief executives (CEs), the second level represents the chief executive officer (CEO), the third level represents the chief operating officer (COO) for Customer Services (CS) and the COO for Support Services (SS), as well as the general manager (GM) for Human Resources (HR), whereas at the fourth level — underneath the COO for CS and SS — comes a number of business units, each headed by GMs, senior managers, or managers. The CS units look after all types of front-office customer transactions and include a number of units, namely, major, business, residential, and new business development units. On the other hand, the SS units work toward supporting all customer units in offering back-office services to customer transactions and include units such as IT support, finance support, engineering support, and services support units.

Corporate Culture

The ability, willingness, and readiness of people to create, share, and transfer knowledge heavily depend on the corporate culture and business integration. Although many attempts have been made at GTCOM to encourage knowledge sharing, it seems that there is still a lack of cultural preparedness for intradepartmental knowledge sharing that was aggravated by lack of business integration across different silos, which had its profound adverse effect on interdepartmental knowledge sharing.

The knowledge-sharing culture at GTCOM has been hindered by additional factors; among these are position/power differences, lack of self-confidence, fear of loss of power or position, and/or misuse or “no use” of knowledge-sharing collaborative technologies. An example of the misuse of knowledge-sharing technologies is when an employee finds hundreds of e-mails waiting for him/her in his/her “in-box” simply because other employees kept on forwarding received e-mails to him/her whether these e-mails concern him/her or not. A customary practice of the no use of knowledge-sharing collaborative systems may be evidenced by an employee who asks his/her boss or another colleague on how to invoke a particular computer procedure instead of searching the intranet for retrieving such a command.

SETTING THE STAGE

Description of KM Context

GTCOM has traditionally been product focused and overwhelmed with supply-side issues rather than customer-side needs. Until GTCOM made a serious effort to under- stand its customers better, its initiatives designed to improve efficiency and effective- ness in the customer interface had little chance of success.

The description of KM context provides an exploration of what customer knowl- edge is, assesses who hold and should hold that knowledge, outlines KM problems, identifies KM directions needed, sketches the overall KM plan, and assesses the way in which that plan relates to KM problems.

What is CK?

Customer knowledge (CK) refers to understanding customers’ needs, wants, and aims when a business is aligning its processes, products, and services to create real customer relationship management (CRM) initiative. Sometimes CK can be confused with CRM. Although there could be some overlap, CK works at both micro and macro levels and includes a wider variety of less structured information that will help build insight into customer relationships. CK should include information about individuals (micro) that helps explain who those individuals are, what they do, and what they are looking for, and should also enable broader analysis of customer base as a whole (macro). Similarly, CK may include both quantitative insights (i.e., numbers of orders placed and value of business), as well as qualitative insights (tacit or unstructured knowledge that resides in people’s heads).

The aim of building up a strong body of CK is to enable GTCOM to build and manage customer relationships. CRM is an interactive process that achieves optimal balance between corporate investments and the satisfaction of customer needs to generate the maximum profit. CRM emerged as an amalgamation of different management and infor- mation system (IS) approaches, and entails the following processes (Gebert, Geib, Kolbe, & Brenner, 2003):

• Measuring inputs across all functions, including marketing, sales, and service costs as well as outputs in terms of customer revenue, profit, and value;

• Acquiring and constantly updating knowledge on customer needs, motivation, and behavior over the lifetime of the relationship;

• Applying CK to constant improvement of performance through a process of learning from successes and failures;

• Integrating marketing, sales, and service activities to achieve a common goal;

• Continuously contrasting the balance between marketing, sales, and service inputs with changing customer needs in order to maximize profit.

CK that flows in CRM processes can be classified into three types:

1. Knowledge about customers: accumulated knowledge to understand customers’ motivations and to address them in a personalized way. This includes customer histories, connections, requirements, expectations, and purchasing pattern (Dav- enport et al., 2001).

2. Knowledge for customers: required to satisfy information needs of customers.

Examples include knowledge on products, markets, and supplies (Garcia-Murillo & Annabi, 2002).

3. Knowledge from customers: customers’ knowledge of products and services they use as well as about how they perceive the offerings they purchased. Such knowledge is used in order to sustain continuous improvement, for example, service improvement or new product development (Garcia-Murillo & Annabi,2001).

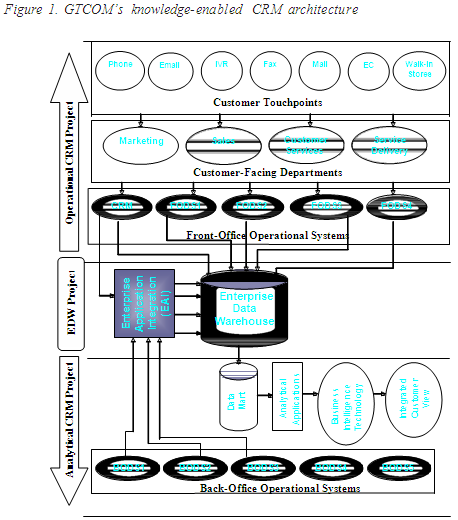

Knowledge about customers is gathered through interactions with customers through processing of customer orders as well as through different customer interaction channels such as phone, e-mail, interactive voice recognition (IVR), fax, mail, e-com- merce, and front-office stores (Figure 1). Operations knowledge about customers, for example, customers’ personal information and purchasing history are held in computer- ized operational data stores (ODS), that is, billing and provisioning data stores, and accessed by staff of these units. For example, each time a customer makes contact with the company, the customer’s needs, as well as the actions taken to satisfy these needs, represent information that may be captured and processed to benefit future customer interactions.

The knowledge about customers should be used to determine what to offer, when to offer, and how much to charge. In the long term, the company has to design new products, offer new services, compete in new markets, but even in the short term, the top salesperson could get sick or be headhunted. What companies currently know about their customers may not be sufficient in order to build and sustain stronger relationship with customers. Companies may need to put in processes and systems to gather more information and data about who their customers are, what they do, and how they think in terms of future purchasing decisions. Therefore, analytical, or deduced, knowledge about customers such as prediction of customers’ expectations and future-purchasing patterns, using advanced computer models and business intelligence (BI) systems is becoming a prerequisite to establishment of strong customer relationship.

Knowledge for customer sources relate to personal knowledge possessed by employees themselves or related to employees’ work such as corporate manuals, guidelines, memos, and meetings. Knowledge that resides in people’s heads can be extracted through person-to-person contacts or through the usage of computer-sup- ported collaborative work (CSCW) technologies, that is, intranets and Lotus Notes, or through e-mails.

Knowledge from customers is another important knowledge for GTCOM that is collected through market surveys.

Therefore, the focus of this case study will be on the most vital form of business knowledge, namely, knowledge about customers and will be referred to as KAC from now on.

Who Hold and Should Hold CK?

Comprehensive CK is created through acquisition and processing of fragmented information found in files and databases specific to the particular application which was designed to process whatever transactions were being handled by the application, for example, billing, sales, accounting, and so forth. Currently, each of GTCOM’s customer contact/delivery channels (e.g., phone, e-mail, fax, store) as well as front-office depart- ments (marketing, sales, and customer services) was operating as a silo with its own island of automation; information from each customer contact/delivery channel was owned as a separate entity by that unit. However, with each unit having its own information, leveraging information across the myriad of customer contact channels was not carried out nor was it possible to provide a consistent customer service experience. For example, a customer may telephone a call center to inquire about a transaction conducted through the Web site only to be told to call the Internet department.

GTCOM does have knowledge about its customers, but frequently this knowledge is in a fragmented form, difficult to share or analyze, sometimes incomplete, and often unused for business decisions. Advances in ICT are increasingly providing GTCOM with opportunities to support customer service operations, and integrate KAC through several contact/delivery channels.

Direct users of KAC are power users at customer-facing departments, namely, sales, marketing, and customer services. Managers of these departments currently hold KAC, but that knowledge doesn’t provide analytical 360-degree view of customers. In addition to power users, there are other users with authorized access to GTCOM’s KAC. These users are as follows:

• Basic users: operational staff at the clerical level

• Administrative users: IT people

• Executive Users: senior managers, GMs, and CEs

The organizational structure of GTCOM does not reflect the needs for effective utilization of knowledge resources. No special unit was found in charge of promoting KM activities and programs where knowledge ideas can be computerized and shared across different departments. In addition, no person was found in charge of the generation, storage, sharing, distribution, and usage of KAC, that is, there is no Chief Knowledge Officer (CKO).

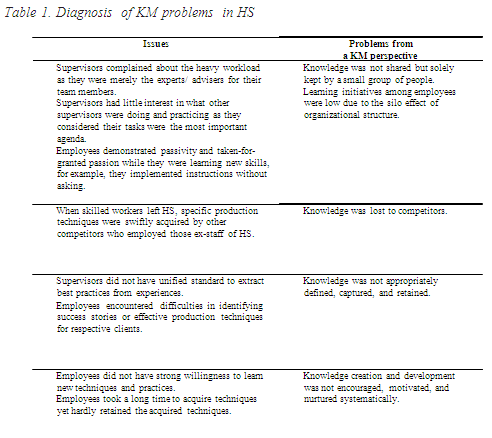

KM Problems

The problem faced by GTCOM in creating a customer-centric business was that its organizational structure was centered on multiple isolated silos or functions, which led to fragmentation of KAC. Multiple silos represent multiple obstacles that undermine full exploitation of enterprise-wide business knowledge. A silo or stovepipe structure is a function-based form of organization, supported with islands of data, which does not promote communication across departments or units. Information on customer demo- graphics and usage behavior, for instance, were scattered among numerous databases, which forced users to query multiple systems when an answer to a simple query was required or when making a simple analysis or decision related to customers.

KAC-related challenges that face GTCOM are as follows:

• Current ICT systems are unable to create complex KAC required by the business decision makers for facing fierce competition;

• Increasing demand for multidimensional customer view;

• Diverse data sources and platforms, that is, Windows, LINUX. UNIX, impeding customer data management.

Directions Needed

There is a need for GTCOM to fill a gap between what it thinks customers want and will put up with, compared to what customers really want and will go to its competitors for. Management of KAC requires effective capture of customer information, conversion of information into useful relationships, and efficient dissemination of knowledge to the places within the organization that need it most for decision making. Management of KAC requires the usage of processes and tools that build and distribute that knowledge.

This requires implementation of an enterprise-wide solution that relies on a single comprehensive data repository, namely, Electronic Data Warehouse (EDW), utilized by multichannel customer service contact/delivery points in order to achieve true enterprise data integration. The EDW is a comprehensive resolution of customer service issues over any and all channels, and a single customer view across the entire enterprise containing all information about the customer, their transactions, and the data they are likely to require during those transactions.

Successful management of a single customer view requires formulation of compre- hensive KCRM strategy that translates GTCOM’s mission and vision into a long-term customer-centric course of action. The objective of the desired KCRM initiative is to capture and organize comprehensive KAC, allow it to be shared and discussed, and to build customer relationships now and over the longer term. A comprehensive KCRM may entail the following components:

• Identification of business/units requirements

• Readiness assessment (manpower, technology, finance, etc.)

• ICT infrastructure upgrade

• Implementation of knowledge-based technology solution

• Organizational transformation

• Cultural change

• Measurement and evaluation of performance metrics

• Change management

Overall KM Plan

Although GTCOM’s overall KM plan is not found at a formal, corporate-wide level, several KM activities were conducted but rarely categorized as KM. However, a customer-centric KM plan has been formulated, clearly articulated, and formally ad- dressed through many formal KM undertakings. One manager clearly explained the fact that the overall KM initiatives at GTCOM were predominantly informal, fragmented, and not part of a corporate knowledge plan or strategy. In his words:

I think we are at the stage where we need to formalize it [KM]. It [KM] is being addressed in general and informally on the basis of ideas we are linking to corporate objectives. So there is nothing specifically to say; like in the past we came with TQM [time quality management], we wanted to introduce this TQM concept into the organization or process reengineering and staff like that, they would be addressed within the departments’ sections. We will say these are the targets: better customer satisfaction, revenue growth, efficiency, and corporate image.… So we gave the owners and the concerned people the chance to come up with the ideas; we do not go to them with the exact solution because it is them who know what is happening in their department sections, and our role is basically to explain to them to think out of the box.

GTCOM adopted a mixture of codification and personalization approaches in its KM activities, but the codification strategy prevailed over the personalization strategy. The following is a description of KM activities undertaken by GTCOM, grouped according to the three pillars of knowledge: people, process, and technology.

People

Job rotation is almost the only notable human-based initiative formally undertaken by GTCOM. The company has placed a high value on applying job rotation principles for several years now. Not only did it transfer people within the same department but transferred them into other departments or into joint ventures outside the country. One manager maintained that “Engineers who are working in HR [Human Resources] and HR people who are working at marketing, and we have finance people who are serving in the front office. This is the way that we have been adopting perhaps not to the degree that we would like because not everybody is prepared to the challenge but 2% of our employees, that is our KPI [key performance indicator], will rotate annually. And we have managed to achieve not exactly 2%, but something close to that, and we are happy with it, but we would like that to be expanded.”

Processes

Sporadic initiatives regarding the sharing of best practices and lessons learned are conducted at GTCOM. For example, the IT department holds an annual review of projects whereby lessons learned and selected best practices are reviewed and distributed to participants. The concept of best practice is also applied to customer service by scripting and compiling frequently asked questions, which are used at the call center as the best practice or standard proven solution for problems presented by customers.

Voice of the customer (VOC) is a KM initiative that aimed at assessing customer satisfaction using a market survey. There are many variables that go into it; it is huge, and is carried out annually. It explores customers’ feelings and level of satisfaction toward a great number of things, including wait time; accuracy of bills; the level of the knowledge and the courtesy and the attitude of the technicians, account managers, help

desk, SMS news, call center staff; prices; communication; and branding. Once the VOC knowledge is captured, it will be properly disseminated and reported to top-level executives for management actions. GTCOM has got a project champion who is basically a person who looks after the survey results, ensures there is an action plan, and ensures that the action plan is implemented.

ICT

GTCOM undertook several ICT-based KM activities. It introduced a new module called the Competency Dictionary or Performance Management Review module as part of the human resource management system (HRMS). The module enables employees to use their terminals to assess their competencies from their own point of view; then their line managers assess them again. This knowledge map allows identifying the gap between the required knowledge and the existing knowledge. The gap is used as a knowledge repository to take HRM decisions related to promotion, transfer, rotation, training, and recruitment. Finally an employee self-service allows access to completed training in the last two years, application to loans, and other services.

Another initiative was project portals, where every project at the company opens a session in the intranet and links the financial area, the project manager and all members of the project. It allows sharing documents and exchanging e-mails. This initiative aimed at creating a collaborative environment for sharing knowledge and work in progress. Similarly, every department has a home page in the intranet to join members of the department and to spread information such as procedures, templates, reports, and folders.

Computer Supported Collaborative Work (CSCW) solutions such as intranets, Lotus Notes, and document work flow systems were also utilized by GTCOM. The intranet supported knowledge dissemination in various ways. Employees heavily use e- mail and Lotus Notes for e-mail, calendar, contacts, and memos to organize meetings, events, and deadlines. The Integrated Document Management System (IDMS) covers document management and work flow and allows moving documents from one place to another when there is a need for approval, for instance. It is still used only in purchasing and in human resource management for performance appraisal review, but it is planned for usage in other areas in the company.

The KCRM is a major technology-based KM program formally conducted at GTCOM. It aims at understanding the “customers’ lifetime value,” and includes three projects: the EDW, operational CRM, and analytical CRM projects. Details of the KCRM strategy will be provided in the Case Description section.

Connection Between Overall KM Plan and CK Problems

Only two of the many KM activities, namely, the VOC and KCRM, formally addressed KM problems. However, knowledge from customers obtained through the VOC is not as valuable, comprehensive, and timely as KAC obtained from the KCRM. Many advanced analytical features such as customer profiling, segmentation, one-to- one selling, cross-selling, up-selling, campaign management, individual pricing, risk analysis, sales prediction, loyalty analysis, and easy customization. In the words of one manager, “It was not possible to bring about an integrated, one single view of the customer by solely focusing on market research activities. The worry was certainly that competitors will come and we certainly have to have competitive edge over competitors, a competitive edge over the customers is our database. Nobody will know our customers’ behaviors, who they are, where they live, when they make the call, but us.”

Additionally, when market researchers go and interview people to generate knowl- edge from customers as part of the VOC initiative, the results of interviews cannot just be taken as the right solutions. The KCRM intends to make a contribution to that, but again the challenge is to analyze the CRM reports, and to extract knowledge from customers the way users want when there are so many variables to consider. For example, when studying the potential demand for a new product, the need is to understand and make the best guess for a market demand, and if the tool is not used properly, then wrong results might come about.

CASE DESCRIPTION

The desired goal of the customer-centric KM plan of GTCOM was the acquisition of cross-functional customer-centric knowledge in order to help it sustain competitive advantage in a highly competitive and dynamic business environment. The focus of this part of the case study will be on providing details of the KCRM components as well as evaluation of the progress made leading to an identification of new or remaining challenges.

KCRM Strategy Fit within Customer-Centric KM Plan

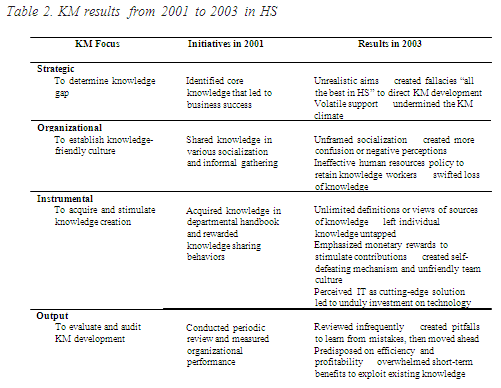

In 1998/1999, GTCOM foresaw that knowledge was key to being able to establish long-term relationships with customers and improving profitability in the impending competitive environment. In 2001, it decided to initiate the development of a threefold KCRM strategy composed of the EDW, operational CRM, and analytical CRM projects to be able to manage its customer-centric knowledge resources.

The development process of the customer-centric KM plan involved several decisions and activities, which are as follows:

1. Transformation toward a customer-centric organization

2. Organizational restructuring to align its structure with the new business strategy

3. Streamlining the value chain of most processes

4. Formulating an action program or business case which involved the following activities:

a. Correction and cleansing of customer data (e.g., customer names, addresses, ID numbers, etc.)

b. Enhancement of customer contact channels

c. Establishment of KPIs to include factors such as return on investment (ROI), head count reduction, speed of customer service, and response rate to customer calls

Although GTCOM has no solid overall KM plan, a customer-centric KM plan derived from the vision of improving customer relations has been articulated. Real customer relationships are formed through interaction and by anticipating user needs, not by providing custom products. Therefore, KCRM has been adopted as an enabling strategy for the achievement of that vision. The KCRM strategy will provide GTCOM with a mechanism to further understand customer behavior and anticipate customer

demand for its telecom services across all sales and service channels, and respond quickly to changing customer needs.

The vastness and complexity of customer-centric knowledge required in today’s service operations demand advanced technology capabilities. There is no doubt that today’s ICT power has opened the door to a new breed of codified knowledge that can help in addressing customer-centric knowledge problems, that is, EDW and CRM, and it is obvious that ICT has dominated GTCOM’s customer-centric KM plan.

KCRM strategy aims at providing GTCOM with an integrated environment to track its sales opportunities, build accurate sales forecasts, provide an outstanding multichan- nel customer service, and deliver speedy fulfillment of customer orders. “Service is proving to be a key differentiator in the region’s increasingly competitive telecoms sector, and GTCOM’s CRM initiative is targeted at achieving one integrated approach toward serving our customers through a multitude of channels,” commented one IT manager. The CRM program manager noted, “CRM is expected to give [GTCOM] a single, updated view of our client base, enabling us to create more targeted sales offerings while providing enhanced service capabilities.”

However, in light of fierce competition facing GTCOM, there is a need to do much more and much faster to increase its customer-centric knowledge base, invest in training their staff, and take advantage of the new ICT for acquiring and disseminating knowledge throughout the company. GTCOM also needs to carefully analyze the potential costs and benefits of introducing ICT-based customer-centric knowledge programs, and adapt these ICT solutions to its KM and corporate context. Also, one needs to remember that KCRM is not only a technology solution to customer-centric knowledge problems. Rather, it is a long-term integrated strategy that combines processes, people, and structural changes.

KCRM Architecture

The KCRM strategy was enabled by three ICT-based solutions: operational CRM, EDW, and analytical CRM (Figure 1). The operational KCRM is composed of three layers. The first layer is customer contact/interaction channels or “touch points,” that is, phone, e-mail, integrated voice recognition (IVR), fax, mail, e-commerce, and person walk-in retail stores. The second layer represents customer-facing departments, that is, marketing, sales, and customer services departments. The third layer is composed of several front- office operational systems:

• CRM: Fixed telephone line service provisioning system (replaced the old CSS

provisioning side)

• FODS1: Fixed telephone line billing (replaced the CSS billing side)

• FODS2: Internet protocol billing

• FODS3: Prepaid mobile telephone line service provisioning

• FODS4: Postpaid mobile telephone line provisioning and billing

The second part of the KCRM is the EDW. Incoming transactional data from all front-office systems as well as many back-office operational systems feed into the EDW. The EDW operates as follows:

1. Extracts data from operational databases, namely, sales, service, and marketing systems.

2. Transforms the data into a form acceptable for the EDW.

3. Cleans the data to remove errors, inconsistencies, and redundancies.

4. Loads the data into the EDW.

In addition, there is an enterprise application integration (EAI) layer that was decided to be there to address the problem of diverse customer data sources and platforms. It integrates the front-office CRM provisioning system with the three back- office billing systems, namely, BODS1, BODS2, and BODS3, which then feed into the EDW. While all front-office ODS applications feed data into the EDW, only three out of five major back-office ODS applications feed into the EDW. Main back-office application systems are as follows:

• BODS1: Geographic information system (GIS) billing system (integrated with the EDW)

• BODS2: Mediated billing for fixed telephone lines (integrated with the EDW)

• BODS3: Back-office billing gateway for mobile telephone lines (integrated with the EDW)

• BODS4: Enterprise resource planning system (ERP)

• BODS5: Human resource management system (HRMS)

The third major part of the KCRM architecture is the analytical KCRM, which is composed of data marts created from the EDW, followed by analytical applications using BI system, and finally development of an integrated customer view. Data mart is customized or summarized data derived from the data warehouse and tailored to support the analytic requirements of a business unit/function.

EDW Project

The EDW is a subject-oriented, time-variant, non-volatile (does not change once loaded into the EDW) collection of data in support of management decision processes (Inmon, 1996). The EDW represents a “snapshot” or a single consistent state that integrates heterogeneous information sources (databases), is physically separated from operational systems, and is usually accessed by a limited number of users as it is not an operational system. EDW holds aggregated, tiny, and historical data for management separate from the databases used for online transaction processing (OLTP). The EDW is a repository of data coming from operational legacy systems, namely, customer care, billing system (including the three customer profiles: IT, GSM, and fixed line billing), finance system, account receivables, and others. The EDW was thought to be a strategic system and major enabler for GTCOM’s continued success in the fierce competitive environment.

The EDW has become an important strategy in organizations to enable online analytic processing. Its development is a consequence of the observation that opera- tional-level OLTP and decision support applications (online analytic processing or OLAP) cannot coexist efficiently in the same database environment, mostly due to their very different transaction characteristics.

Data warehousing is a relatively new field (Gray & Watson, 1998) that is informa- tional and decision-support-oriented rather than process oriented (Babcock, 1995). The strategic use of information enabled by the EDW helps to solve or reduce many of the negative effects of the challenges facing organizations, reduce business complexity, discover ways to leverage information for new sources of competitive advantage, realize business opportunities, and enable quick response under conditions of uncertainty (Love, 1996; Park, 1997).

GTCOM realized that it could not continue to run business the same traditional way by using the same old ICT and the same old focus of a product-led business in a highly competitive and turbulent business environment. The competitive nature of today’s markets is driving the need for companies to identify and retain their profitable customers as effectively as possible. GTCOM perceived the key to the achievement of this objective was the usage of rich customer data, which could be sitting unused in a variety of databases.

EDW Planning and Initiation Stage

In 1998/1999, GTCOM had some foresight that knowledge was crucial to establish long-term relationships with customers. Although the company’s leadership commit- ment played a key role in the implementation of the initiative, the main driver for EDW initiative was the fierce competition due to deregulation of the local telecommunications market that was announced in 2001 but took effect in 2003.

GTCOM has its own approach for approving new business initiatives and convert- ing ideas into concrete projects. From a business management perspective, new initia- tives at GTCOM pass through three major stages. Prior to the commitment of resources and initiation of a project, GTCOM makes sure that it adds value; managers present a business case to a senior management team called the Capital Review Board to agree on the capital expenditures, timing, and expected outcomes. The business case covers all the business requirements (BRs), prioritization of BRs, and how they fit within the corporate objectives. The requirements revolved around this open question: “What are the most important pieces of information that if you have today, would help you make better or more informed decisions?”, for example, customers’ information which includes type of customers, age, location, nationalities, gender, education and professions, and geographic distribution, and products’ information which represent historical data for all services and products.

Business questions (BQs) were then established. The BQs are documents that help in modifying the standard logical data model (LDM) to meet GTCOM’s business requirements. One BQ example is, “Which customers generate most of the total traffic?” Then, BQs are carefully examined and prioritized to determine what information is needed for each BQ. Also “owners” of BQs are assigned, so that any further discussion of meaning can be conducted on a one-to-one basis rather than a full-house meeting.

Once the EDW project was initiated, the second phase took place wherein the Project Review/Management Committee evaluated achievements compared to the plans approved in the first phase. When a project was completed, it was checked in terms of its deliverables, cost, and time. Since many of the KM initiatives were supported by ICT, they also followed a specific development and implementation process based on the methodology used by the IT department.

GTCOM then tendered the EDW system and selected a vendor, who formulated strategies and presented experiences and recommendations of processes and structures to best exploit knowledge. In the first quarter of 2001, the initial stages of the project began. To understand business processes and objectives, the vendor of the EDW redefined processes, identified key business deliverables, and prioritized them into about 100 business cases, for example, customers, products, revenue, traffic, and sensitivity analysis. The vendor played a leading role in being the main source of knowledge for GTCOM and in partnering with business units to define their business requirements. The vendor formulated strategies, presented them to management, and came up with experiences and recommendations of how to best exploit knowledge in terms of processes and structure. At the same time, GTCOM formed a committee in order to align the system to business objectives in terms of who should be getting what access, what sort of information should be going on it, and how to structure the project phases.

EDW Design and Customization Stage

The EDW project is a very multifunctional and multitasking endeavor that tran- scends functional boundaries, for example, technology, product, marketing, market research, and finance. In 2000, GTCOM formed different committees to oversee the first phase of the project. These were the Business Intelligence Steering Committee (BISC) representing GMs (high-level senior managers) and Project Management Committee (PMC) consisting of the IT project manager and key business representatives from marketing, sales, back office, and customer care. There were also subcommittees looking into technical details of the system such as format of reports, quality of data, and others.

Soon, GTCOM finalized the design and started customizing the EDW and transfer- ring information from the source systems into the EDW system. The end of 2002 witnessed the completion of the first stage called Increased Business Value. During 2003, the second phase (Expansion and Growth) began.

The high-level design of the EDW was composed of the following:

• The data warehouse itself, which contains the data and associated software;

• Data acquisition software (back-end), which extracts data from legacy systems and external sources, consolidates and summarizes the data, and loads it into the data warehouse (operational side);

• The client (front-end) software, which allows users of business intelligence, tools such as decision support systems (DSS), executive information systems (EIS), data mining, and customer relationship management (CRM) to access and analyze data in the warehouse (analytical side).

The design and customization process involved the following decisions/activities:

• Customizing the standard;

• LDM of the vendor to meet GTCOM’s BRs and rules;

• Designing a high-level data sourcing and architecture design to support the established BRs;

• Designing data access architecture and user access points;

• Designing management and maintenance structure, which includes system, man- agement, user administration, security management, as well as backup, archive, and recovery (BAR).

EDW Testing and Support Stage

The testing process consisted of activities such as defining the test environment, defining test cases and test data, assembling the components to be tested, executing the test, analyzing results, correcting identified problems, and revising/updating the testing process throughout the life of the project.

The support function involves a number of processes and tools that will be used to give the users the access priority adequate for them according to the service level agreement (SLA). This is done via a number of processes and tools.

EDW Implementation and Operation Stage

This harmonizes well with the concept of EDW, which is an interdisciplinary endeavor that needs to transcend functional boundaries, that is, technology, product,

marketing, market research, and finance, and it capitalizes on shared knowledge and expertise from different business units.

EDW Implementation Team

The EDW project actively involved senior management, IT managers, business managers, and the vendor during the development process. Although knowledge users are business people from various functions, an IT manager at the beginning championed the project. Soon they understood that it had to be business driven and one of the general managers was appointed as the sponsor. The technical mind-set of IT people may not fit the business nature of the EDW project; EDW was part of a business strategy, not just a suite of software products. The following roles were performed by the EDW implementation team:

• Business representative: this role provides the leadership necessary for project success, facilitates the decision-making process for current and emerging business needs and requirements, as well as facilitating users’ training and project budget- ing decisions. The role provides link between the business side and the IT side. While he/she doesn’t need to understand the details of system installation and configuration, business representative must be aware of CRM configuration and maintenance requirements. The GM for the Residential Customer Business unit handled this task.

• Executive sponsor/owner: this person is a major business player who plays both the role of sponsor and owner, provides the link between the project manager and upper management, guides funding and financing decisions, as well as decisions about when and where to deploy the CRM system. This person must understand the details of the installation, configuration, and schedule. The EDW sponsor was the manager for the Customer Marketing unit.

• Project manager: the project manager directs the work, makes things happen, and works with the vendor. This person must understand the details of the installation and configuration, and the schedule. The EDW project manager played this role.

• Project team leader: the role of this person is same as that of the business representative but from the IT point of view. This person is responsible for coordinating the IT side of the project with business needs and requirements. A database administrator handled this task.

EDW Content

The EDW is a data-based rather than a process-based system. Therefore, it does support data capturing and processing but not business processes. The data captured by the EDW relate to the following entities:

• Customers: relate to residential or business customers (age groups, living areas, etc.).

• Products: represent the number of mobile or fixed telephone lines, Internet lines, and so forth.

• Traffic: related to the usage behavior of customers (in terms of volume, duration, and time of calls).

• Revenue: referred to the amount of money generated per category of customers, products, age groups, or living areas.

• Sensitivity analysis: derived information that results from advanced analysis of the previous components.

Many reports can be generated from the EDW. Products/services reports, for instance, provide the following information:

• Revenue breakdown as one-time/recurring usage for each product family per quarter;

• List of customers based on the number of offers a customer has;

• List of customers who do have a selected product/s but has other selected product/s;

• List of customers and the products (leased equipments) and the age of the equipment;

• Sold products in the last 12 months, in addition to cross-selling reports;

• Top/bottom N products based on the number of customers subscribed to those products;

• Customer-level profiling based on bills issued, payments, overdue amount, and number of bills with amount overdue;

• Segmentation of customers based on the average current charge per invoice ranges;

• Top N rank customers based on revenue, usage/recurring/one-time revenue by party type;

• Revenue growth over a period of 12 months with respect to customer category.

CRM Project

The CRM project was composed of two parts: operational and analytical. The operational CRM project was delivered in May 2004. The goal of the CRM project was to enable GTCOM to focus on its “customers’ lifetime value.” Typically, operational CRM has the potential to respond to customers’ priorities in terms of their value and being able to answer customers promptly and efficiently and would feed at the inbound and outbound directions into the EDW (bidirectional). To do so, the agent dealing with them would have online information about their identity, spending, products and services, and needs. And on the other hand, anything customers ask online would be captured into the marketing side of the CRM straight away by the front-end units such as call center and customer care, and will be used for customer segmentation and profiling by the analytical CRM.

The analytical side of the CRM is scheduled to start the planning phase in September 2004, and is due to be delivered in 2005. CRM feeds the transactional processing data into the EDW and then conducts analytical processing on these data. The analytical CRM typically includes OLAP, data mining (DM), and business intelli- gence (BI). However, only the BI option has been part of the analytical CRM at GTCOM. Analytical CRM provides power users with sales cubic view of their customers through slicing and dicing, back-end marketing management activities, such as campaign man- agement and sales management; and allows users to feed on certain business rules for customer groups into the operational side, as well as predict future trends and behaviors and discover previously unknown patterns. It also facilitates marketing campaigns and surveys. The rest of discussion will be confined to the operational side of CRM.

CRM Implementation

The operational CRM development process passed through the following major decisions and/or activities:

• Approval of the business case and project budget after analyzing its benefits, costs, and potential risks;

• Selection of a vendor and ICT application. The vendor was itself the consulting company that managed the implementation of the CRM initiative, drawing on the software company’s extensive expertise in the business needs of the telecoms sector;

• Integration of the old technology (CSS provisioning and billing system) with the

CRM project in the transitional phase;

• Identification of project implementation team members who represented major business units as well as the IT unit;

• Establishment of best work flow practices for provisioning of services;

• Mapping of customer data flow in line with the new process flow;

• Deciding on the right time to discard the old customer service system (CSS), a system for telephone line provisioning and billing, and the right time to go live with the new operational CRM system, as well as deciding on the criteria of acceptance of the system from the vendor.

CRM Implementation Team

The implementation team of the operational CRM project performed the following roles:

• Business representative: this role provides the leadership necessary for project success, facilitates the decision-making process for current and emerging business needs and requirements, as well as facilitating users’ training and project budget- ing decisions. This role provides link between the business side and the IT side. While he/she does not need to understand the details of system installation and configuration, the business representative must be aware of CRM configuration and maintenance requirements. The GM for Customer Services handled this role.

• Executive sponsor/owner: this person is a major business player who plays both roles of sponsor and owner, provides the link between the project manager and upper management, guides funding and financing decisions, as well as decisions about when and where to deploy the CRM system. This person must understand the details of the CRM’s installation, configuration, and the implementation schedule. The business representative was a senior manager for IS Development and Analysis.

• Project manager: the project manager is the person who directs the work and makes things happen. This person must understand the details of the installation and configuration, the implementation schedule, work with other team members and understand their contributions, and work with the outside vendor. The CRM project manager handled this role.

• System owners: set up and configure hardware, and install operating systems and supporting software. Different IS specialists in charge of ODSs handled this role.

CRM Processes

Unlike the EDW, the operational CRM system is a process-based system that automates customer-facing business processes, and is accessed by a large number of users who operate or manage the operational systems as well as their ODSs. It automates the following groups of processes:

• Sales processes

• Service processes (both fault and complaint processes)

• Marketing processes

• Call center/contact channels processes

CRM Content

In addition to automating business processes, the operational CRM system cap- tures the following types of transactional data:

• Customer demographic data

• Service fulfillment information

• Sales and purchase data and their corresponding service order number, status, etc.

• Service and support records

• Profitability of products and customers

• Other types of customer-centric information

Organizational Transformation

Alongside the KCRM program, GTCOM undertook an organizational transforma- tion initiative in its quest for achievement of customer-centric business. In 2000, GTCOM felt that it was time to reengineer business processes by cutting out the non-value- adding ones, and integrating ISs together. There were many fragmented or stand-alone systems that were doing many important things but were not “talking” to each other.

Starting from 2001, GTCOM foresaw the need for a transformation of the organiza- tion from engineering-led to customer-led. The end of 2002 witnessed the completion of the first stage called Increased Business Value. In 2003, several work teams looked at the various functions and processes for possible improvement and reengineering. Phase 3 of the organizational transformation program, known as Get Ready, was a continuation of the first and second phases that was almost paralleled with the EDW project. Phase

3 mainly sought to help GTCOM face the business competition by transforming GTCOM

from product-led to customer-led business.

An outside consultant was called in to lead the organizational transformation process. However, the consultant faced some resistance from employees, especially when the issue of restructuring was tackled. Restructuring became part of the organiza- tional politics and inertia emerged as a result.

One of the specific restructuring initiatives launched by GTCOM under the newly emerged customer-led form was a “Knowledge Exchange” to increase the cross-func- tional cooperation and exchange of knowledge between sales (customer-facing or front- end) and product development (marketing-oriented or back-end) divisions. These two divisions were used not to maintain cooperation and exchange of knowledge with each other as they had a culture of “we got our own things to do; you got your own things to do.”

As a direct response to the liberalization program of telecommunications services, GTCOM has been going through a transitional rebalancing program that started in 2003 and is planned to continue until the end of 2005. At the beginning of 2003, the sales and product divisions were merged, and as a result of the combined knowledge of these two units, GTCOM has launched its new Mobile Price Plan on June 2003. This whole undertaking would not have been possible in the past with all of the silos or stovepipes in place.

Following the implementation of required organizational adjustments in the transi- tional period, GTCOM will be operating in a fully competitive environment by the end of

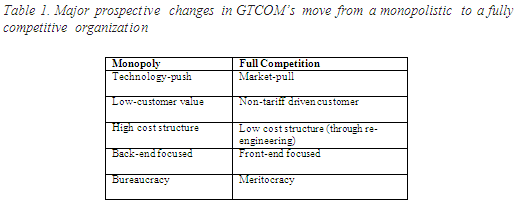

2005. Table 1 summarizes the major prospective changes that are due to take place following the transformation of GTCOM from a monopolistic to a fully-competitive business.

Results

Financial Performance

On the financial performance side, GTCOM has done extremely well so far in its ability to meet the turbulent and competitive environment. The main favorable result witnessed following the implementation of the KCRM strategy was that it offered GTCOM good financial performance results during the first quarter of 2004. Since GTCOM transformed its business and implemented KCRM, its net profits climbed to about 25.2% against the same period of last year. This increase is attributed to a year- on-year rise in gross revenues of 5%, and a reduction in costs largely due to nonrecurring exceptional items related to restructuring, which were successfully implemented by GTCOM in 2003.

Operational Performance

Unlike its good financial results, GTCOM’s performance was not encouraging at the level of operational excellence (i.e., service time, lead time, quality of service, productiv- ity) and satisfaction/loyalty of stakeholders (customers, employees, etc.). It faced and/ or is still facing the following problems:

• System’s inefficiency and customers’ expectations: the operational CRM could not capture basic customer data; people at network department, for example, could not trace the work flow of sales order processes, which in turn, adversely affected the ability to meet customer expectations. This inefficiency would result in longer order fulfillment or service completion time, low productivity, customer dissatis- faction, and possible defect of customers to competitors.

• Work flow problems: the logical work flow of sales order processes across business units is as follows: Sales, Network, Programming, Private Branch Exchange (PBX) between users and network, Installation, and Accounts, respec- tively. Service delivery time now is on average one to two weeks, but was less than one week under the old CSS provisioning and billing system.

• Testing/migration problems: during the migration/testing period which lasted for couple of days (roughly between seven to ten days), many data did not go through

the operational CRM, as their data fields were not validated by the system. The nonvalidated data had to be rekeyed manually into the system. The computer system was of no use for the whole transitional migration/testing period, so all costumer operations were processed manually.

• Vendor-related problems: although it is a world-class vendor with extensive experience in ICT solutions, the vendor underestimated project complexity and responsibilities. This resulted in missing the delivery target three times, and then followed by a decision by many employees to quit their jobs.

• Ineffective change management: in addition to the projects implementations team, there was a dedicated change manager; however, this role was ineffective. The concept of change management was new to GTCOM, and it could not afford to continue funding the post, so the post was cancelled.

• Management problems: GTCOM changed the CSS system into CRM in a critical period of time when the market was liberalized. It was very dangerous to phase out the CSS system when nothing was clear on the negative consequences on operational excellence and satisfaction of stakeholders. It had also been decided to proceed with implementation although it was known that the system was not effective and incapable of meeting the objectives of the CRM strategy and its KPIs.

CHALLENGES

Although GTCOM had made some positive moves toward changing the organiza- tion from being engineering-led to customer-led, especially in light of changes in its business environment, it still faces a number challenges with respect to the effective management of its knowledge for continued business success. The challenges are as follows:

Overall KM Strategy

There was a need to formulate organization-wide formal KM strategy and programs for learning best practices and for the development of new projects. The KCRM initiative at GTCOM seemed to be created and used on the basis of “technology push,” introduced through vendors, rather than “market pull,” as a mere response to real business need. The KCRM technology components were driving, instead of enabling, the KCRM strategy and its KPIs. One manager admitted that “suppliers try to push their new products and then there is stage of filtering, studying, and analyzing where there are subjectivities and different opinions.” The development of an organization-wide strategy for the genera- tion, sharing, distribution, and utilization of knowledge is becoming imperative for GTCOM’s continued success in today’s competitive market.

Although it can be said that GTCOM did a good job in putting up the required ICT infrastructure in place, however, it did not develop a robust business solution in terms of knowledge processes that allowed exploiting the information provided by the imple- mented system. One manager explained, “I don’t even think we have the process to look at the customer from A to Z. I think the mistake maybe [GTCOM] has made is that we have been very good in putting up the system, but even the underlying process of capturing the needs of customers hasn’t been well though of and hasn’t been implemented properly.”

Another manager argued, “Unfortunately, this is what I have to say that with respect to EDW: we have done the systems and IT side very well, but the other side of it — the knowledge aspect of it — exploiting that knowledge, exploiting that source, and also the skills aspect of the people, there is quite long way to go.”

Corporate Culture

Corporate culture is widely held to be the major inhibitor or facilitator for creating and leveraging knowledge assets in organizations. Low-trust cultures constrict knowl- edge flow, and companies that have conducted organizational transformation or downsizing, such as GTCOM, face a particular problem in this regard. These companies need to rebuild trust levels in their culture before they can expect individuals to share expertise freely without worrying about the impact of this sharing on employees’ value to GTCOM. Such changes require paying considerable attention to the supporting norms and behavioral practices that manifest trust as an important organizational value (Long & Fahey, 2000).

Since 2002, there has been more encouragement for internal knowledge sharing through committees as a result of transformation from a product-centered to a customer- centered business, and from bureaucratic to democratic management. This may be due to the fact that GTCOM will no longer be able to enjoy its monopoly in the market, and will have to improve its competitive position through organizational transformation and capitalizing on its core competencies, namely, KAC.

However, monitoring business pressures that were supposed to be drivers for knowledge creation, diffusion, and application did not seem to have helped in total elimination of knowledge hoarding that fears competition and leak of information. One manager argued, “GTCOM has certain visions along that side [KCRM], it is a big project, it takes a long time, needs cultural changes and stuff like that. So that is the challenge we are facing right now.”

Business Requirements

The biggest challenge to the KCRM projects was the determination of corporate- wide business requirements and knowledge strategy. As there was lack of consensus on defining business requirements and goals of every business unit, there was also lack of consensus on defining data elements (e.g., good/bad customer) among business units as every unit may have its own definition of data elements.

Stovepipe Structure

KM is a cross-divisional and cross-functional intricate endeavor. Plans to make better use of knowledge, as a resource, must be built into the structure and culture of the organization in the medium term. KCRM technology alone was not enough to create a competitive advantage unless it has been coupled with the necessary organizational transformation from silo-based to process-based structure, especially in the front-end business operations, and capitalizing on the power of the intellectual assets of people to improve the quality of delivered services while achieving better efficiency and efficacy.

The organizational structure should reflect the needs for better management of knowledge. A special business unit, or a cross-unit task force or team, needs also to be established in order to foster the concept of KCRM in a formal and a holistic approach through experimentation, documentation, sharing, and dissemination of knowledge across different departments. This structural change will allow to improve performance of initiative already in place and to promote new initiative that might be needed, such as the establishment of an electronic library, yellow pages, knowledge maps, that can facilitate the buying and selling of specific knowledge created by workers in different departments within GTCOM.

Stovepipe or silo organizational structure hindered organizational learning among business units, as the organization, as a whole, would not know what it does know. The silo or stovepipe structure led to the fragmentation of activities among many depart- ments, and resulted in the creation of physical and psychological walls separating business functions, for example, information on mobile and fixed phones that appear to be done independently on an ad hoc basis. The functional-based structure of GTCOM was being overemphasized at the expense of knowledge sharing across departments especially in customer services, which are cross-functional in nature.

The workflow of many processes of the CRM system was very slow and not smooth, and streamlining work flow of fragmented processes is still unresolved in many areas. Interdepartmental communication problems (cultural and technological) are still prevail- ing under the multiple-silos structure.

Business Integration

Once they lacked a single information repository, companies have traditionally spent large amounts of time and money writing integration programs to communicate between disparate systems. A variety of technological options exist for the implemen- tation of KCRM projects. The adopted hardware, software applications, and databases for the KCRM initiative need to be compatible and operable with the existing legacy systems. The chosen ICT infrastructure needs also to integrate well with other systems

in the organization. Some adjustments may be required to assure a balance between systems requirements and functionality from one side and flow of business processes from the other side.

Evidence of the ineffective ICT infrastructure is the lack of integration with previous technology initiative and legacy systems. There are several problems with integration. First, integration complexity causes delay. Systems will rarely operate in real time resulting in delays in synchronizing information. This can cause embarrassment to companies and aggravation to customers when updates to one channel are not reflected immediately in the others.

The second problem is that integration adds overhead cost. The integration must be implemented, administered, and maintained independently of the actual customer service applications for each delivery channel. The problems of complexity and costs are magnified each time a change is made to a channel application.

Customer’s Expectations and Satisfaction

In addition to being inefficient in capturing some customer data, the CRM system still suffers from limited storage capacity/lack of scalability, complexity, limited process- ing speed, and lack of technology fitness in terms of growth and implemented capacity of the KCRM projects. These shortcomings of the system could adversely affect customers’ experiences and satisfaction, as well as employees’ morale.

Power Users

Knowledge/power users are people who are responsible for generating knowledge about competitors, external market, products, and so forth, using the EDW initiative. Actual knowledge users of the EDW may include people from units such as sales, marketing, market research, and human resource management, although potential users could include other departments such as product development. As business-wide requirements were not effectively identified, so the knowledge requirements of different business units were not being successfully transferred into data entities, and many units did not seem to be constantly using the system. It seemed that heavy usage of the EDW system was at the marketing and sales function, as the culture in other units may not have favored the usage of the system as a source for generating knowledge. One manager maintained, “I don’t know if the finance people use it enough because they do have a SAP system, I don’t know if it is integrated with the EDW.”

Knowledge users of major KCRM systems, for example, the EDW, at GTCOM need to be expanded to include functions other than sales and marketing, such as finance, operations and logistics, and so forth.

Quality of Data

Following an identification of business needs and agreeing on a definition of data elements of the system, data cleansing should be conducted before putting up the EDW initiative. Otherwise, false indications and misleading information would be the outcome. Data accuracy is very critical as EDW systems retrieve data and put them in the required format, but if the raw data were not completely filtered, then the validity of the project’s information would be at risk. Poor data quality at GTCOM resulted from accumulation of much data inaccuracies over the years, and there is a need for conducting an urgent cleansing of these data.

From a technical perspective, there were great expectations as to the capabilities of KCRM systems, but the systems turned out not to be as successful as expected. The system overpromised but underdelivered as it was hard to use for basic queries due to the unavailability of some data elements in the legacy system and quality of data (some data elements were inaccurate and/or incomplete at the data source and data entry level).

Some managers claimed that project management had not considered some prob- lems from the past and, therefore, problems continue to exist with the new systems. According to one manager, “One of the problems that has happened which we have inherited now putting this integrated knowledge-based systems together is that we know all systems had data corruption in the past, and again [GTCOM] hasn’t properly done enough work to clean that data first and then put into the system. Today, for example, [we are] suffering because [we are] basically doing analysis and generating reports and some of it is not accurate.”

The GM of HR explained the data accuracy problem in the HRMS implementation by saying, “What has happened during our trial period is that at the end of the year, I discovered that some people have got a lot of leave days, this is one of the short comings of self-service because it has not been handled properly at line management level. Then I discovered that a lot of people have days of leave outstanding so I questioned and when we checked with the line managers they say, ‘Oh, I forgot to enter it.’ So instead of you having 20 days leave, you were having 60 days leave, and I said to the person or department, ‘OK, all staff above 20 pay them those days in cash to do the balance and not have more than 20 days.’ You know it would have caused me to make the wrong decision because of lack of responsibility of line management.”

Resistance to Change

The KCRM is a core business initiative that is sensitive to the political environment within an organization. Without complete user support, KCRM projects are doomed to failure. People’s mind-set and resistance to change posed a real challenge to the KCRM program. Some employees did not accept the new system, as it was too advanced for them to cope with. User training was not adequately provided to the right people, at the right time, and for the right duration.

There is a need for new blood as it is too difficult to fine-tune the mind-sets of some employees. More recruitment and training of staff, for example, new graduates, who are capable of absorbing or generating new knowledge, and the incorporation of knowledge creation, sharing, distribution, and usage of knowledge in the performance appraisal of employees could help in the expansion of knowledge usage.

However, GTCOM did not have any formal mechanism for providing financial rewards to members who create, share, or use knowledge. A direct outcome of the lack of financial incentives is the limited willingness of employees to contribute to the knowledge sharing, creation, and leveraging. Changes in GTCOM’s reward system could help in motivating knowledge workers to create, share, and apply knowledge.

Job Losses

The challenge of job losses was a major part of the restructuring exercise. However, one key executive maintained, “That’s not the object of the exercise, but a drop in headcount is inevitable — and I think our employees accept that. It is a fact of life that monopoly phone operators all over the world has been forced to slim down to become competitive. [GTCOM] has a duty to its customers, shareholders and employees — and refusing to face economic facts will do no favors for anyone in the long run. In the future, job security will be related to our ability to retain customers.”

Vendor’s Involvement

It seems that the focus of the EDW and CRM vendors was limited to customizing and implementing ICT tools, but not ensuring that the process and organization elements were in place for effective management of the KCRM project. An effective vendor’s role and involvement, as well as effective management of relationship with vendors are very essential to the KCRM success.

Organizational Roles

The lack of structural mechanism for knowledge creation, sharing, and leveraging made it very difficult for many employees to access particular knowledge or even to be aware that knowledge is out there and needs to be leveraged. The absence of a formal position in charge of KM in the corporate structure, for example, CKO, made it very difficult for one group to learn from other groups outside their business functions. The existence of a position such as a CKO helps in defining a formal methodology in synthesizing, aggregating, and managing various types of CK throughout GTCOM.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The challenge of competition, after many years of monopoly, is shaking off GTCOM and is forcing it to abandon the old product-led traditions of the telecommunication monopoly and, instead, focus sharply on customers and what they want — not what it thinks they should have — in order to please them and win their long-term loyalty. Focusing on customer relations is increasingly becoming a weapon used by many service-oriented firms to face business challenges.